“May I see your vaccine passport?”

That question may soon be asked at New Zealand’s borders as the country steadily reopens to overseas travellers who have been vaccinated against Covid-19.

The International Air Transport Association (IATA) launched a ‘Travel Pass’ late last year. This app informs travellers about the restrictions for entering different countries, contains a database of where to get tested or vaccinated and is capable of storing test and vaccination status data from participating laboratories. IATA isn’t alone – tech giants like Microsoft and health companies like Cigna have teamed up to develop a new smartphone-based vaccine passport as well.

“There are a number of different international initiatives underway and the Ministry has been working with several of these parties, as well as local stakeholders such as Air NZ and Auckland International Airport,” a spokesperson for the Ministry of Health told Newsroom.

“It seems like a very obvious tool,” Helen Petousis-Harris, an associate professor in vaccinology at the University of Auckland and the chair of the World Health Organisation’s Global Advisory Committee on Vaccine Safety, told Newsroom.

“There are already apps out there in the world that can actually access your health data. It doesn’t necessarily have to be a piece of cardboard, but it’s not a new concept, it’s been around for a long time with Yellow Fever and smallpox, once upon a time.”

Amidst the fervour to reopen the globe, tech has emerged as a reliable way to verify someone’s vaccination status. As with digital contact tracing, which saw debates over apps versus wearables and QR codes versus Bluetooth, there are a number of technical disagreements on how vaccine passports should work.

But Andrew Chen, a research fellow on technology and society at Koi Tū – The Centre for Informed Futures at the University of Auckland, says the tech isn’t the largest issue. The big question, he says, is what the passport is meant to do and how our border policy might evolve to respond to the rollout of vaccines overseas.

Policy settings

The Government has yet to make any announcements on how border restrictions may change for people who have been vaccinated. Although vaccines rolled out in some countries at the end of last year, it may have been a moot point because New Zealand’s medicines regulator, Medsafe, had yet to approve any of those jabs.

From next week, however, Medsafe may well give the go ahead to the Pfizer/BioNTech mRNA vaccine. Millions of people, particularly in the United States and United Kingdom, have received the first of two Pfizer doses and hundreds of thousands have completed the full course.

If Medsafe believes the Pfizer vaccine provides immunity against Covid-19 and people with that vaccine would like to come to New Zealand (whether they are New Zealanders or not), should they be able to go through a shortened stint in MIQ or skip it altogether? The Ministry of Health and Covid-19 Response Minister Chris Hipkins have been tight-lipped about any potential border changes.

“I can’t see that happening quickly,” Hipkins said on Wednesday.

“I’ve always said that, in terms of our border restrictions, vaccination will play a role here at some point. I don’t think that’s likely to be sudden or quick. I think it’s likely to happen over a period of time. But it’s still too early to get into what that might look like.”

Speaking to Newsroom late last year, all Hipkins would say is that New Zealand would likely see a staged reopening via successive safe travel zones. Even that seems on the rocks now, however, with the Prime Minister pulling back from a country-to-country level bubble with Australia and entertaining state-by-state bubbles instead.

A spokesperson from the Ministry of Health didn’t answer questions from Newsroom about potential changes to border rules.

In determining those policy settings, one has to look at the science, University of Auckland microbiologist Siouxsie Wiles says. At the moment, we don’t yet know whether any of the vaccines simply prevent severe disease from Covid-19 or whether they provide what experts call sterilising immunity – preventing people from catching and therefore spreading the virus in the first place.

Even in the former scenario, sick people with no coughing or sneezing symptoms will spread the virus less. But if people can still be infected and spread the virus after vaccination, then opening up the border to immunised travellers could put the country’s elimination status at risk.

(Wiles also disclosed a potential conflict of interest to Newsroom, saying she had been involved in an effort around the start of the pandemic to develop a technological solution for contact tracing, test results and, eventually, vaccination status. The funding bid submitted for the project was rejected and is no longer ongoing.)

Wiles and Chen both emphasised that vaccine passports should only be used for international travel – not to restrict people from going to the supermarket or schools if they haven’t yet been vaccinated.

“The Government has already been really clear they’re not going to make it mandatory, and when you start talking about stuff like that you completely freak out people who are vaccine hesitant,” she said.

“You risk basically damaging all sorts of good will, doing those kinds of things.”

Only open to the first world

There’s also a moral issue with a policy that opens the borders for vaccinated people but keeps them closed for those yet to be immunised. Globally, there are not enough vaccines being produced this year to immunise the world population.

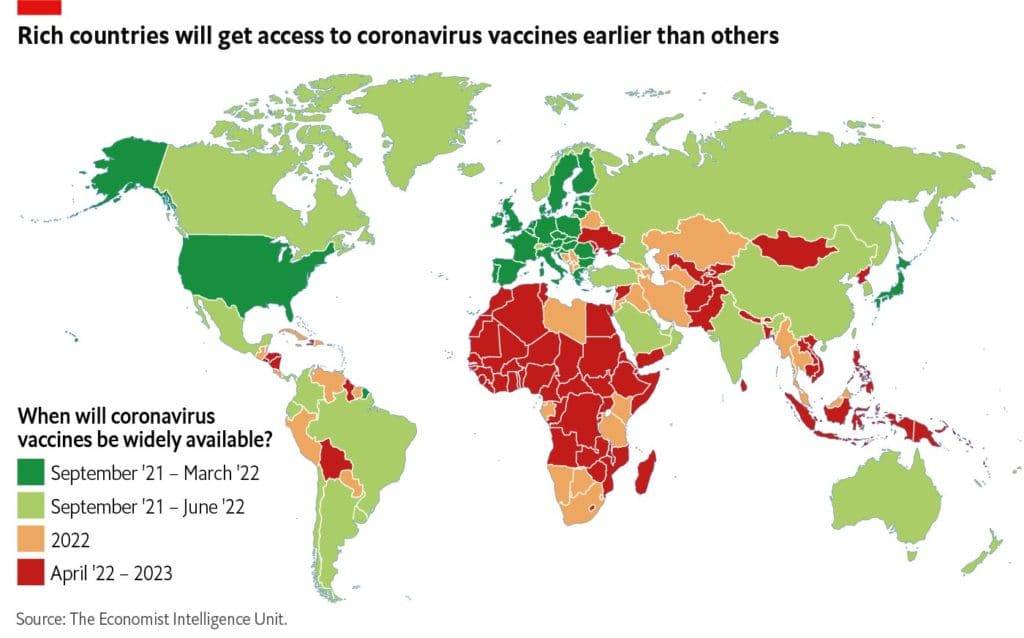

First-world countries are likely to get the vast majority of this supply. An analysis by the Economist Intelligence Unit found countries in Africa, the Middle East and South East Asia were more likely than others to begin mass vaccinations from 2022 or later.

The United States and much of Europe, however, would see vaccines widely available by September 2021 and likely wrap up their mass campaigns by March in 2022.

“Many high-income countries have made advance purchases of billions of doses of future vaccines for their populations, leaving limited potential supplies for others. This undermines efforts to ensure sufficient availability and inclusive distribution around the world,” Amnesty International found in a report on inequitable access to vaccines, released in December.

And in September, Oxfam reported that governments representing just 13 percent of the world’s population had purchased half of the global vaccine supply to date.

In other words, by only opening our borders to those who have been vaccinated, we risk only opening our borders to travellers from the developed world, while continuing to keep out people from developing countries with lesser or no access to vaccines.

“That is why we should be fighting for equitable access to the vaccine for everybody,” Wiles said.

“And also why we should back off, here in New Zealand, because there are countries that need it more than we do.

“It’s a freedom of movement debate. We’ve already put in a whole bunch of freedom of movement restrictions, some more explicit than others,” Chen told Newsroom.

The tech questions

Wiles said the inequitable distribution of vaccines globally could lead to the evolution of new variants of the coronavirus that evade some vaccines. (For more on that, see the first part of this series on whether New Zealand should stay at the back of the vaccine queue.)

In that scenario, vaccine passports could be even more important as they would be able to record the type of vaccine the person had received. mRNA vaccines, like those developed by Pfizer and Moderna, can be easily tweaked within a matter of weeks to respond to new mutations; indeed, Moderna is developing a booster shot to handle the B.1.351 variant identified late last year in South Africa. Vaccine passports could be used to track these boosters and other alterations as well, to help inform border policy.

However, these mRNA vaccines are primarily going to be distributed to developed countries. Therefore, even the evolution of an immune-resistant coronavirus variant could further entrench inequities – rendering vaccines delivered in poorer countries less effective while wealthier countries shrug off the impacts.

In addition to recording the specific vaccine delivered, passports might also include the date it was delivered in the event that some vaccines end up providing only short-term immunity.

Chen says there are electronic passports that would likely verify vaccination status by referencing a central database of some sort. The alternative, he suggests, is users self-reporting their vaccination status – but that could easily lead to fraud.

“If that’s not going to be the case, then you’re basically relying on, firstly, national health agencies having a centralised digital record of vaccinations – which most don’t have and, in New Zealand’s case, is something that we’re building right now. And secondly, all of those systems having APIs that are available for whoever to call,” he said.

“The question for me comes back to what is a vaccination passport meant to be used for? And therefore, how reliable or how accurate does that information need to be? When we’re talking about any case [of Covid-19] being unacceptable, then that’s the hard bit. Because the risk tolerance is so low, you have to ask, how can we necessarily guarantee that this information is valid and correct?”

There’s also the question of whether passports might interact with databases in a standardised way or on a country-by-country basis.

“There are multiple ways to solve that problem technically. A big part of that will be whether you need international interoperability or compatibility. These are processes that often take many years, if not 10 years, to come to agreement. It is a tall order to end up with international compatibility.”

The Ministry of Health spokesperson told Newsroom that work was underway on international standards.

“Work has been underway for the past four months to resolve a number of issues. These include countering fake documentation and creating the standards required to meet international obligations. New Zealand is part of the World Health Organisation’s standards setting process. We expect this to form the basis of a global interoperable solution. It’s in New Zealand’s best interests to work with our international partners on this to make sure the solution works for everyone,” the spokesperson said.

“We expect if these standards are able to be implemented, they would apply as much to New Zealanders going overseas as those returning home.”

Without international compatibility, each passport app would have to individually vet each country’s national database and devise a unique way of communicating with it. That could also further inequity, as first-world countries would likely be at the front of the line for this.

Another option, instead of using a centralised state database, is to deliver the vaccination record to the app when the vaccine is delivered, via the lab or agency that gives the person the jab. Many American efforts are liaising with hospitals and pharmacies because health records may not be centralised beyond that point of care.

This, however, could be less secure, Chen says.

“Most people would accept that this is something that a government has to do. The private sector might be a provider or a consultant, but it’s not like May, in New Zealand, when we had 30 different QR code providers.”