Although recent weeks have seen a spate of climate-fuelled natural disasters around the world, relatively little news coverage of these events has correctly identified climate change as partly responsible.

New Zealand is no different, with a Newsroom analysis of mainstream media coverage of the West Coast flooding finding that 80 percent of articles made no mention of climate change or global warming. Of the remainder, 8 percent contained language noting that climate change will increase the likelihood of extreme weather in the future and just 12 percent actually said climate change had a role in the weekend’s flooding.

Climate scientists have made themselves available to speak about the issue and have been clear that climate change made what would already have been a bad storm worse.

“This weather event was certainly worse due to climate change,” Nathanael Melia, a senior research fellow at Victoria University of Wellington’s Climate Change Research Institute, told Newsroom on Monday.

He said that the water holding capacity of air increases by 7 percent for each degree of warming we experience. “Globally, we are at about +1.27°C now due to human-induced climate change. So when these systems slam into our mountainous terrain, they have more rain to drop.”

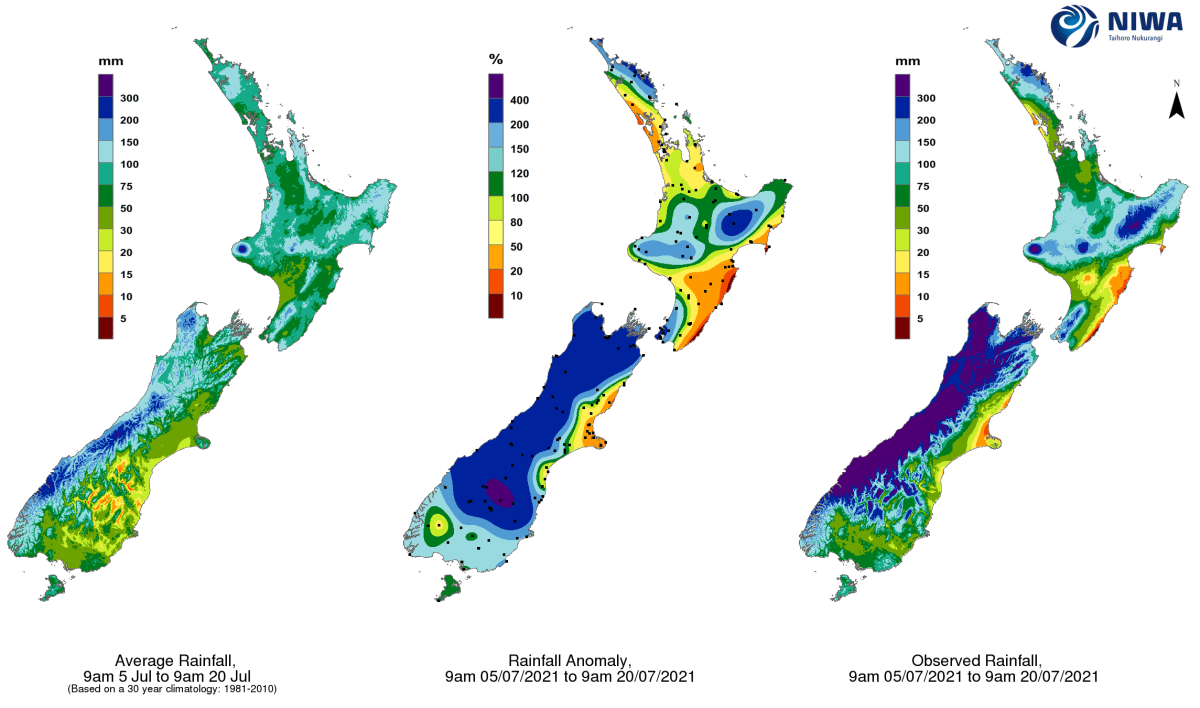

Luke Harrington, who also works at the Climate Change Research Institute and helped author a paper on climate change attribution last year, said the flooding was the result of a phenomenon known as an atmospheric river. This is a narrow corridor of moisture in the atmosphere, funnelled from the tropics to higher or lower latitudes.

Harrington said recent research found New Zealand “is one of the most susceptible countries in the world, when it comes to extreme atmospheric river impacts”. That’s partly because of the increased moisture in the air mentioned by Melia and partly because climate change has strengthened westerly winds in winter. In other words, atmospheric rivers that would already have led to flooding and damage in a world without climate change are now wetter and faster.

When they then slam into the Southern Alps, it’s a perfect recipe for disaster.

“If you were to pick any time of year or location in New Zealand where an extreme rainfall event lasting several days shows a robust signal of becoming more intense and more likely because of climate change, I would pick the West Coast of the South Island in the winter time,” Harrington told Newsroom.

Harrington’s comments were also made available to other reporters via the Science Media Centre, along with expert reaction from other scientists. Judy Lawrence, another senior research fellow ad the Climate Change Research Institute, was quoted by the Science Media Centre as saying, “The total disruption we saw from the heavy rainfall over the weekend on the West Coast and Marlborough is consistent with a changing climate that is warming and able to hold more water before dumping it. We can expect more of this.”

Despite the ready availability of expert comment, relatively little news coverage of the flooding attempted to explain it as more than a catastrophic Act of God. Certainly some of it was down to forces of nature and bad luck, but anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are a culprit too.

This isn’t an isolated instance. Environment reporter Chase Woodruff analysed 149 articles about a June Colorado heat wave that predated the Pacific Northwest heat wave by a week and found that just six referred to climate change in any way.

“The direct equivalent would be if local media had spent the last 18 months reporting on overwhelmed hospitals and elevated death rates and shuttered businesses and mass layoffs, and only mentioned Covid-19 in 4 percent of those stories,” he wrote.

New Zealand’s coverage turned out to be slightly better than that, but just 20 percent of articles making any mention of climate change and even fewer doing the legwork to attribute some of the flooding to it is still a dismal result. If damage on a similar scale had been partially wrought by a Chinese cyber attack, the root cause would hopefully have received a much wider airing.

Part of the issue is that as journalists we find it extremely easy to put ourselves into silos – local news reporter, foreign correspondent, housing reporter. But just as those silos were blasted open by the Covid-19 pandemic – with everyone from business reporters to political editors grappling with transmission dynamics and contact tracing systems – they’ll have to be loosened for the climate crisis.

As climate journalist Emily Atkin told CNN’s Brian Stelter last month, after the North American heatwaves and before the flooding in Europe, New Zealand and now China, “Everyone should be a climate reporter. And if you are not a climate reporter right now, you will be.”

Climate change is already so wide-ranging as to make those silos irrelevant. Its fingers are behind extreme weather events and efforts to combat it are driving economic innovation and pushing farmers to protest in the streets. Energy, technology, business, finance, health, housing, agriculture and more are all driving climate change and will experience the impacts of it.

That makes it complex to cover, but part of the role of journalism is to unravel complex topics for readers. Embrace the challenge that this nuance presents, don’t pave over any mention of climate because it’s simpler that way.

Climate change is not (just) an environmental problem. It is an economic, social and political crisis – and it should be covered like one.