It’s complicated and fraught. There are entrenched commercial interests and passionate environmental and community protesters. There are people worried about endangered birds and surf breaks and coastal flooding, and there are people worried we won’t be able to build the homes and infrastructure we need.

There are people who say there is a technological solution and we need courageous leadership to change the entrenched model.

And in the middle are governments trying to make the right decisions.

The topic is sand mining – digging up vast quantities of sand from beaches, or rivers, or off the coast, to feed an insatiable appetite for bridges, roads, glass, for re-sanding beaches and reclaiming land, even for electronics. But mostly for concrete for new buildings.

So when submissions closed last Friday on resource consent applications to dredge up to nine million cubic metres of sand from off the coast off Pakiri beach, north of Auckland, hundreds of New Zealanders found themselves part of what has become a worldwide protest movement.

The Guardian, for example called sand mining “the global environmental crisis you’ve probably never heard of”; there have been books written, including Sand Stories by Kiran Pereira, there’s a hard-hitting documentary called Sand Wars, and the topic engenders headlines like “The truth behind stolen beaches” and “Why the world is running out of sand”.

In New Zealand, the biggest and most current fight is over the white sand at Pakiri, an east coast beach north of Auckland.

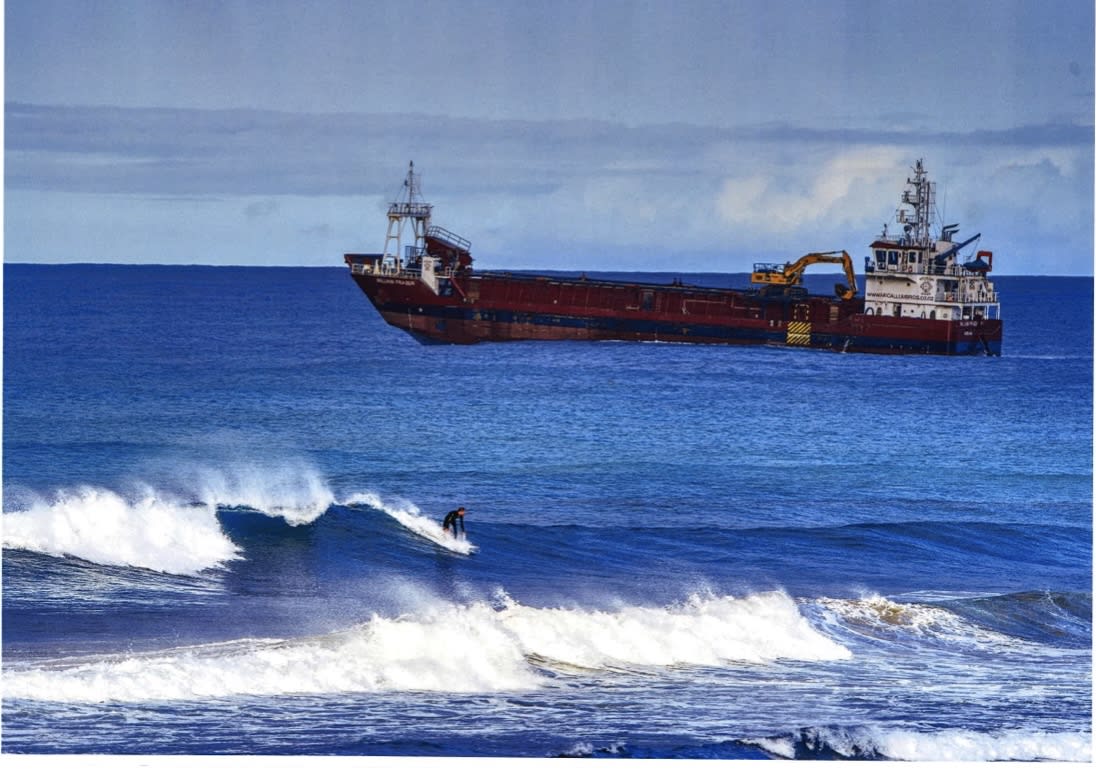

Up to three times a day on some days, a sand dredging boat trawls up and down off Pakiri beach, vacuuming up the seabed. Any unwanted material is spewed back into the sea and the sand is collected on the boat, which heads to central Auckland where the sand it sent off to local concrete manufacturers .

Thousands and thousands of cubic metres of sand are dredged from the sea every month.

A long history

Evidence suggests the sand at Pakiri built up thousands of years ago, when the Waikato River flowed into the east-facing Firth of Thames.

When a volcanic eruption 2000 years or so ago forced the Waikato westward – it now meets the sea on the other side of the island – it changed the sediment flows to Pakiri. And therein lies one of the major bones of contention between the dredgers and the local community and protestors – and the subject of many pages of technical documents the council will need to wade through: whether the sand is being replenished or not, and whether any additional sand is enough to replace the millions of tonnes being taken away.

Sand has been taken from Pakiri for more than 100 years. Various Auckland beaches wouldn’t be nearly so good to sunbathe on without top-ups of Pakiri sand and the ‘white gold’ has been used in local landmarks from the Sky Tower to the Waterview Tunnel, from the Central Interceptor sewage project to the Harbour Bridge.

But as volumes of sand being taken from the beach have increased, so have the concerns of local people, who started to fight the dredgers, worried about eroding dunes, seabed degradation, damage to surf breaks and the impact on some seriously endangered fairy terns.

In the early 2000s, locals won a victory from the Auckland Council, which turned down a sand dredging application. But the mining companies fought back, won the battle in the Environment Court and again when a Court of Appeal case was dismissed.

At the heart of that protracted battle was that vexed question of whether those tonnes of sand being barged away to Auckland were being naturally replaced by sediment coming in and shells being worn down. The dredging company, McCallum Bros’ scientists said they were; the Auckland Regional Council and a local group called Friends of Pakiri Beach said the evidence accepted by the Environment Court was full of factual errors.

Multi-year dredging consents meant sand mining continued unobstructed off Pakiri beach for more than a decade.

But now existing permits have either expired or will soon be up for renewal – and battle lines are drawn again.

Nine million cubic metres of sand

Over the next few months, McCallum Bros, the largest supplier of sand for concrete in the Auckland region, will be back in front of the Auckland Council to plead its case in three separate applications – first to mine sand close to shore, second to take it from 15-25m offshore, and third to dredge from 25m and beyond.

Between the three applications McCallum is looking to take up to nine million cubic metres of sand over the next 35 years.

It’s hard to visualise nine million cubic metres of sand, but maybe it helps to know that one of those trailers you hire to bring soil or compost – or sand – back from the building supply store holds about half a cubic metre.

So McCallum wants to take 18 million trailer loads of sand from the Pakiri coastline over 35 years. Actually maybe that doesn’t help much, but suffice to say it’s more sand than has ever been taken before.

Auckland Council hasn’t released dates for the three application hearings in 2022. The first of the three processes, for mining furthest out, actually started last year, but the decision was delayed first by Covid and then because the hearing panel asked for bathymetric reports – detailed studies of the sea bed where the drilling has been taking place.

The panel – and the local community groups – say without these studies it’s impossible to judge the impact of previous dredging on life under the water.

Submissions on the second and third applications – for the near-shore and mid-range dredging – are the ones which closed last week. Meaning 2022 is likely to be the crunch point for the future of sand mining at Pakiri, and possibly beyond.

Our critical need for sand

McCallum argues the Pakiri sand is crucial to meet Auckland’s growing demand for homes and infrastructure.

“Currently Auckland produces about 1.8 million cubic metres of pre-cast and ready-mix concrete. This requires approximately 790,000 tonnes of sand on an annual basis,” the company says in a website answering frequently-asked questions about its Pakiri sand mining.

“McCallum Bros Ltd (MBL) supplies at least 45 percent of that volume, which equates to 780,000 cubic metres of concrete. Much of this concrete is used in high strength infrastructural projects. On top of that, there is demand for at least another 200,000 tonnes of sand for the industrial, landscape, turf and equestrian markets in the Auckland Region.

“Given Auckland’s current housing shortage, infrastructure needs, and growth forecasts provided in the Auckland Unitary Plan, it is estimated that demand for sand is likely to increase by at least 40 percent when conservative growth figures are used. Based on growth in the last two years at 6 percent, it is expected to almost triple to as much as 2.8 million cubic metres by 2043.”

Pakiri sand gives the Auckland construction industry confidence of “an ongoing and reliable supply of sand to produce the concrete needed to support continued infrastructure development required by a growing city”, McCallum says.

Fragile ecosystems

On the other side, locals – and there were more than 650 submissions opposing the first resource consent application, as against just four who submitted in favour – mostly want sand mining to stop completely.

“Once the sand is gone, it’s gone.”

Jessie Stanley, Save Our Sands

“The removal of sand offshore from Pakiri has been going on for too long and over the years I have seen the dunes fall away into the sea and the marine life dwindle,” says David Joyce, whose submission is typical of hundreds of others. “Research shows us that dredging and removal of sand affects fragile ecosystems. If this happens for another 20 years we may not have a safe beach at Pakiri much longer. Let us take 20 years to replenish our oceans.”

Jessie Stanley grew up in Pakiri and is a community spokesperson for lobby group Save Our Sands. She says Pakiri is a ‘closed circuit’ environmental system. “Once the sand is gone, it’s gone.”

“The beach has eroded so quickly lately, it has deeply shocked our community. And that is without any consideration of future changes because of global warming.

“There is available science now that can be used to model future changes to coastal systems based on rising sea levels, but [McCallum] has not undertaken any of this.

“Also deliberately separating the three consents has made this process easier for McCallum as that doesn’t take into consideration the total amount of sand taken. At the hearing we only look at the effects of one consent at a time.”

McCallum says it is looking to reduce the number of consent applications from three to two – the one to dredge more than 25 metres offshore and either the new mid shore (15-25 metres) or the existing inshore (5-10 metre) consent, though the quantities may not change.

Mixed opinions

McCallum Bros argues mining at Pakiri Beach has not damaged the dunes.

“Aerial photos have found the beach has actually grown in the last 50 years as more sand washes onto the beach than is washed away. In fact, the sand dunes at Pākiri Beach have moved seawards by 22 metres (an average of 0.4m/year) during the past half-century, despite sand extraction taking place.”

Locals dispute those findings, arguing among other things that sand dunes moving forward are a sign the beach is being sucked into the sea to fill the holes the dredging is making. And they worry about what’s going on under water.

“Independent science using sonar readings has found insanely huge trenches on the seabed- 6km long and 20m wide, but when Kaipara put in scientific results for the hearing in April last year, that information wasn’t there,” Save Our Sands spokesperson Jessie Stanley says.

She talks about ‘Kaipara’ because the offshore permit was previously owned by quarrying and industrial company Kaipara Ltd, though the actual dredging has been done by McCallum for years. In October Kaipara got out of the sand mining business altogether, deciding owning a sand extraction permit “was not in line with their company direction or interests in the short or long term”.

It sold the permit and application to McCallum, which now control all three applications.

Lack of oversight

Save Our Sands, which brings together a number of local groups opposing the sand mining, is also worried about the lack of oversight of how McCallum operates at Pakiri. “Sand extraction is run by an honesty box – McCallum tells the council how much sand they take.”

SOS sent Newsroom a sample of a sand extraction report McCallum sends to Council each month. The data – for June 2020 – shows company dredgers were operating 58 times during the month – sometimes three times in one day.

The report says the quantity of sand taken each time was almost always 450 cubic metres, although occasionally it was 350 cubic metres, with a monthly total of 25,200 cubic metres.

It’s not clear how that very specific 450 cubic metre figure is derived – McCallum hadn’t replied to Newsroom’s query by the time this story was published. But Auckland Council accepts it doesn’t verify the data.

“To date, we have not found reason to question the volumes submitted,” says Amanda De Jong, the council’s manager of compliance monitoring. “Should concerns be raised in regard to the reliability of information submitted, then we would consider what actions were necessary to ensure full compliance with the extraction limitations.”

The message is different from the Hauraki Gulf Forum, a statutory body made up of ministers, representatives from five councils and Tangata Whenua and charged with the conservation and sustainable management of the marine park. The Forum wrote its first letter to Auckland Council’s resource consents team in June 2020. In the letter it asks for clarification of how sand mining at Pakiri fits with provisions in the 2000 Hauraki Gulf Marine Park Act around “the maintenance, protection and, where appropriate, enhancement of the natural, historic and physical resources of the Gulf”.

When, by March 2021, the forum still hadn’t received a reply from the resource consents team, it wrote another, more strongly-worded letter.

“Since our June letter we have been receiving with increasing urgency and frequency expressions of deep concern from members of the public, submitters, iwi, Resource Management Act lawyers and other experts,” the forum’s co-chairs Nicola MacDonald and Pippa Coom wrote.

The second letter talked about a lack of consideration of Māori values and Treaty rights, limited consideration of climate change impacts, concerns about monitoring existing sand extraction consents and “the lack of an applicable baseline of sand/aggregate removed”.

Then last week, noting it hadn’t received an answer to either of its two previous letters, the forum wrote for a third time, restating its concerns about the continuing sand extraction and addressing some barbed comments at consenting officials.

“Following presentations from both proponents and opponents of the applications, some forum members queried the absence of an overarching sand supply strategy by the consenting authority,” the letter, copied to Mayor Phil Goff, said.

“We also note that central Government recently pledged to extend benthic [relating to the bottom of a body of water] protections in the Hauraki Gulf from seafloor-impacting fishing methods. There may be benefit from Council/Crown coordination on this issue to ensure a common approach to seafloor protection – be that from dredging, trawling, dumping or sand extraction.”

Sand mining 101

What exactly is the big deal with sand mining globally? And how exactly do you get to a worrying scarcity situation for what is the world’s third most plentiful natural resource by volume, after air and water. Depending on whose numbers you use, sand extraction is thought to be worth $100 billion-a-year and the industry has grown massively since 2000, as the world’s appetite for buildings and infrastructure has grown, particularly in China and India.

The Guardian estimated in a 2018 article that of the 15-20 billion tonnes of sand used annually, about half goes into concrete.

“Our need for concrete is such that we make almost 2 cubic metres worth each year for every man, woman and child on the planet.”

But surely, we are talking sand here – that quintessential metaphor for an infinite resource.

“When astronomers seek to impress upon us the size of the universe, they speak of stars being more numerous than grains of sand,” Guardian reporter Neil Tweedie said. “There are quite a few grains, as it happens – 7.5 x 10 to the 18th power, according to researchers at the University of Hawaii. That’s seven quintillion, 500 quadrillion – give or take the odd trillion.”

So it takes some mind games to realise sand is a surprisingly finite resource, or rather that the sort of sand that goes into concrete is running out.

Blame the uselessness of deserts. Because while there is a lot of desert sand around, you can’t use that for construction – its wind-weathered grains are too small and too smooth.

Making concrete with desert sand is like “trying to build something out of a stack of marbles, instead of a stack of little bricks”, author Vince Beiser says in his 2018 book The World in a Grain

The sand mafia

Sand from beaches, sea or riverbeds is rougher and more angular, and makes great concrete. But it’s also being used up at a mammoth rate, Beiser says. His estimate (double that of the Guardian above) is 45 billion tonnes a year, enough sand to cover the state of California.

The burgeoning demand has seen sand prices rise dramatically and a big increase in people making their living digging up and selling sand – both legally and illegally.

“Sand has become very profitable in a short time, which makes for a healthy black market.”

Sand researcher Dr Aurora Torres

“From Jamaica to Morocco to India and Indonesia, sand mafias ruin habitats, remove whole beaches by truck in a single night and pollute farmlands and fishing grounds,” Tweedie says.

“Those who get in their way – environmentalists, journalists or honest policemen – face intimidation, injury and even death. “It’s very attractive for these sand mafias,” says sand researcher Dr Aurora Torres, who is one of the few academics studying this Cinderella issue – overshadowed as it is by climate change, plastic pollution and other environmental threats. “Sand has become very profitable in a short time, which makes for a healthy black market.”

No one’s talking about sand mafias in New Zealand.

But some of the Pakiri mining opponents say they are worried about the way McCallum has operated in the past.

Allegations of non-compliance

Damon Clapshaw is a film financier who has been going to Pakiri for almost 50 years. His family own a share of an organic farm that backs onto the dunes at Pakiri Beach, and Clapshaw is a founding member of Friends of Pakiri Beach, alongside international arbitrator Sir David Williams.

In his submission, Clapshaw alleges McCallum “has breached all of the on-the-water conditions of the inshore consent, for example operating too far north, too far south and other on-water consent conditions.”

More than 50 percent of dredge expeditions “can be shown to have a consent breach of some sort, going back many years and involving hundreds of breaches over hundreds of expeditions,” he says. In addition, McCallum has breached off-the-water conditions of the consent around filing environmental reports and surveys.

“Some of the missing reports are cornerstone documents, being required surveys which are pivotal to baseline and monitor environmental changes,” Clapshaw says in his submission.

McCallum had not responded to Newsroom’s questions about any alleged breaches before this article was published, although Kaipara Ltd mentioned them in its own application for a Pakiri sand extraction resource consent earlier this year.

As mentioned earlier, Kaipara at the time was the owner of the permit for the sand extraction, though all dredging was done by McCallum; McCallum has since bought the permit too.

“Kaipara is well aware of concerns that exist about the implementation of the current consent, and has methodically sought to compose a suite of controls for the new consent that can be relied on to avoid any shortcomings of the past,” Kaipara’s lawyer Morgan Slyfield said in his submission in May.

“Allegations of non-compliance are likely to continue to be made by some submitters in the course of this hearing, and Kaipara will address those allegations to the extent they are relevant to the present application.

“Further, the steps Kaipara has taken over the past two months (in response to alleged breaches), and the steps Kaipara is committing to take under the remaining life of its current permit, and under the new consent (if granted), collectively demonstrate that Kaipara is genuinely and sincerely working to improve the implementation of its sand extraction activity.”

Asked about any possible breaches, Auckland Council’s manager of compliance monitoring Amanda De Jong says that hasn’t been verified.

“The council has not been provided with any evidence that corroborates Friends of Pakiri Beach’s claims around the level of non-compliance, or that the alleged breaches occurred. Recent tracking maps submitted by McCallum have been reviewed and do not indicate that dredging has occurred outside of the consented extraction zones.

“However, we are currently awaiting the results of a Bathymetric Survey commissioned by the consent holder, which will provide additional evidential detail for us to consider. Once this information has been provided, we will decide what action is necessary, if any.”

So is there an alternative?

It’s complicated. Some opponents to the Pakiri sand mining argue Auckland should be getting its sand from a site which isn’t a closed system – like the Kaipara Harbour to the west.

The trouble with the Kaipara sand, McCallum says, is getting it to Auckland needs either a long trip round Cape Reinga, or a lot of truck trips down from Helensville.

That’s expensive, and not great for the environment. McCallum’s website estimates meeting the demand from Auckland’s construction sector with Kaipara sand would need “21,000 return truck and trailer movements every year on the North-western motorway, resulting in increased congestion and an extra 1,340 tonnes of CO2 emissions in the atmosphere.”

Manufactured sand

The other problem with taking sand from the Kaipara Harbour is that you don’t solve the issue of sucking up the seabed, potentially destroying critical habitat for some species, and mining a diminishing global resource.

Instead, some locals say New Zealand should be looking at a more sustainable alternative starting to be used overseas – albeit a solution which will need a shake-up of existing practices: manufactured sand.

Manufactured sand is sand made in quarries from ‘crusher dust’ – some of the fine particles produced as a by-product of the rock crushing process.

The technique isn’t new – manufactured sand has been around for a while, but traditionally crusher dust hasn’t been ideal – it can have particles which are the wrong shape or the wrong size, or contain contaminants like clay.

Then, at the end of the 1990s, Japan began banning dredging, citing destruction of fishing grounds and deterioration of the seabed. Japanese construction companies began importing huge quantities of sand from China, but that just exported the problem, and the Chinese government started restricting the sand trade to Japan.

Instead Japanese companies started working on ways to overcome the problems with using crusher dust to make sand.

By 2015, independent research from Cardiff University showed that “with appropriate adjustments” processed crusher dust could be used as a complete replacement for marine-dredged sand in concrete. Using this method, Japan has reduced its use of dredged sand by 84 percent since 2000.

“It’s critical the council doesn’t just roll over and approve dredging the coast for another 35 years, but looks in detail at the options around manufactured sand, and sends a clear message that dredging is unsustainable.”

Bram Smith, Kayasand

Hamilton-based Kayasand designs and builds crushing and screening plant for quarries, and is the licence holder in New Zealand for Japanese sand manufacturing technology which, the company says, could allow concrete to be made using crusher dust without blending it with natural sand.

The company put in a submission to all three Auckland Council sand mining resource consents and spoke at the hearing earlier this year.

General manager Bram Smith told Newsroom he was hoping the council would look carefully at the alternatives.

“It’s critical the council doesn’t just roll over and approve dredging the coast for another 35 years, but looks in detail at the options around manufactured sand, and sends a clear message that dredging is unsustainable.”

It won’t be easy. Quarrying equipment isn’t cheap, and switching away from mined sand requires a significant change.

Wayne Scott is chief executive of the Aggregate and Quarry Association. While it would be possible to replace natural sand with manufactured sand, he says, “this would be at a significant additional cost and it would be counter productive in that additional aggregate resource would be consumed in producing sand”.

Any move towards more manufactured sand would have to be over the long term, because of the significant capital investment required, Scott says.

“There would also be a significant cost increase in concrete as mix designs would need to change which may involve use of additional cement.”

It’s a catch 22-type situation if you are looking to replace the Pakiri sand, as Kayasand notes in a submission this month.

“Justifying investment in new concrete sand manufacturing processes is more difficult when dredged natural sand is readily available and the status quo is working.”

The wrong economics

Kiran Pereira wrote her dissertation on sand mining and has been working on the topic ever since. She is the author of “Sand Stories: Surprising Truths about the Global Sand Crisis and the Quest for Sustainable Solutions”.

“The true costs of sand are currently not reflected in the price of sand because they are treated as externalities,” she tells Newsroom from London. Environmental degradation, fairy terns, habitat restoration, biodiversity loss.

“Local communities and wildlife are often the ones most impacted. As this is a non-renewable resource in human timescales, it is critical to consider intergenerational equity and the cumulative impact of extraction whenever decisions are made about resource consents.”

Pereira says there are plenty of viable alternatives to dredging “and manufactured sand is definitely one of them.

“Experience has shown that supply often follows demand.”

Back in Pakiri, Jessie Stanley says two petitions – one on the Save Our Sands page, and one on the Greenpeace site have together garnered 12,000 signatures (though some will be duplicates) showing the depth of feeling.

She says locals will keep fighting, even if next year’s decisions go against them.

“It feels like make or break at the moment – they want 35 years more – that is the remainder of my life.”